There are many reasons to rescue an old building—because you have to is one of them, because you want to is another. The new owners of this dilapidated structure teetering over a bay in Blue Hill, Maine, were determined to resuscitate it, despite the fact—as the architects later learned—there was almost nothing left to save.

Built in 1919, it was once a small yacht club on the private property of one of its members. After the club relocated to its current and more commodious location in the 1940s, the building had undergone a number of unsuccessful interventions. By the time Elliott Architects arrived on the scene, the foundation was severely compromised, the superstructure was failing, the interiors were stripped to bare bones, and, of course, it was in a flood plain. The Old Yacht Club was in no way yar.

“Somebody had bought it and attempted to renovate it for residential,” recalls project architect Corey Papadopoli. “So the use had already been changed. We inherited the use, but unfortunately also a building with no maintenance. Everything had changed but the club room. But it’s a unique site and you would not be able to build here again.”

Preserving and transforming the quaint little building into a viable family retreat required fully dismantling it, labeling and numbering all the parts, and storing them on site. Even the chimney came down—before falling down of its own accord—and was set aside and documented for restoration. Doing all this enabled the team to address the dire state of the foundation. It was a heavy lift that benefited from Elliott Architects’ expertise in coastal design and the myriad rules that govern building at the water’s edge.

“Normally FEMA regulations would require the structure to be on posts and piers, but that would have destroyed the integrity of the building, because its major characteristic was appearing to emanate from the ridge,” Corey explains. “There’s another mechanism where FEMA allows for breakwaters and walls. We got permission to buttress the walls of the foundation, as long as we allowed water to move through it. There were existing openings that we were able to leave open. But we found the foundation was 50% on clay and 50% on ledge. We had to go in in sections and pour concrete to bridge stone walls to the ledge and fully support the thing. It was an intricate process just to get the building stabilized.”

Once the building was properly anchored to its site, the team set about building a new engineered wood and steel superstructure in the shape of the old one, reassembling all the usable timbers and sourcing additional ones, replacing the old leaky single-pane windows with matching high-performance ones, and rebuilding the chimney with a reinforced structure and new firebox.

Better Not Bigger

The next challenge was hewing to the old building’s footprint while accommodating a reimagined and expanded program. The clients requested three bedrooms and bathrooms, plus an open kitchen, living, and dining room in the former club room space. They also wanted views of the water, which the original building had not prioritized—after all, the best views in those days were on boats in the ocean, not inside service buildings on the shoreline.

This was all within the architects’ wheelhouse, of course, but there was one big catch: “The real trick,” Corey says, “was to figure out the vertical circulation. The original stair was on the exterior of the building, and we wanted to internalize that.”

Bringing the stair inside would consume vital space needed for storage and other appurtenances of daily life. But coastal architects and builders often think of houses like boat designers do, outfitting every square inch for multiple purposes. The solution for the stair was to turn it a hardworking service wall, containing the powder room, the pantry, the mechanical closet, a coffee bar, and even the refrigerator—at some remove from the kitchen (with the owners’ consent). “Everything is tucked under that stair, it’s like an intricate cabinet with all the stuff built into it,” says Corey.

The kitchen, on the other hand, is designed like freestanding furniture, imposing only lightly on the rebuilt club room’s rugged appeal. To gain extra square footage for the room—and open up views to the water— the architects replaced two largely solid walls with adjoining lift-slide doors pushed into the former covered deck area. When open, the club room converts into a protected porch immersed in water vistas.

Upstairs, old diminutive dormer windows are now large, glazed projections, adding both headroom and long-range views to the bedrooms. Like the industrial kitchen, they are unapologetically modern. “We wanted to draw a very clear line between old and new. The dormers are butt-glazed, laminated structural glass,” Corey explains. “Upstairs is all new, so we used a clear and neutral palette—everything painted white.” The result is serene and calm, like sitting atop a cloud.

No Cars, Please

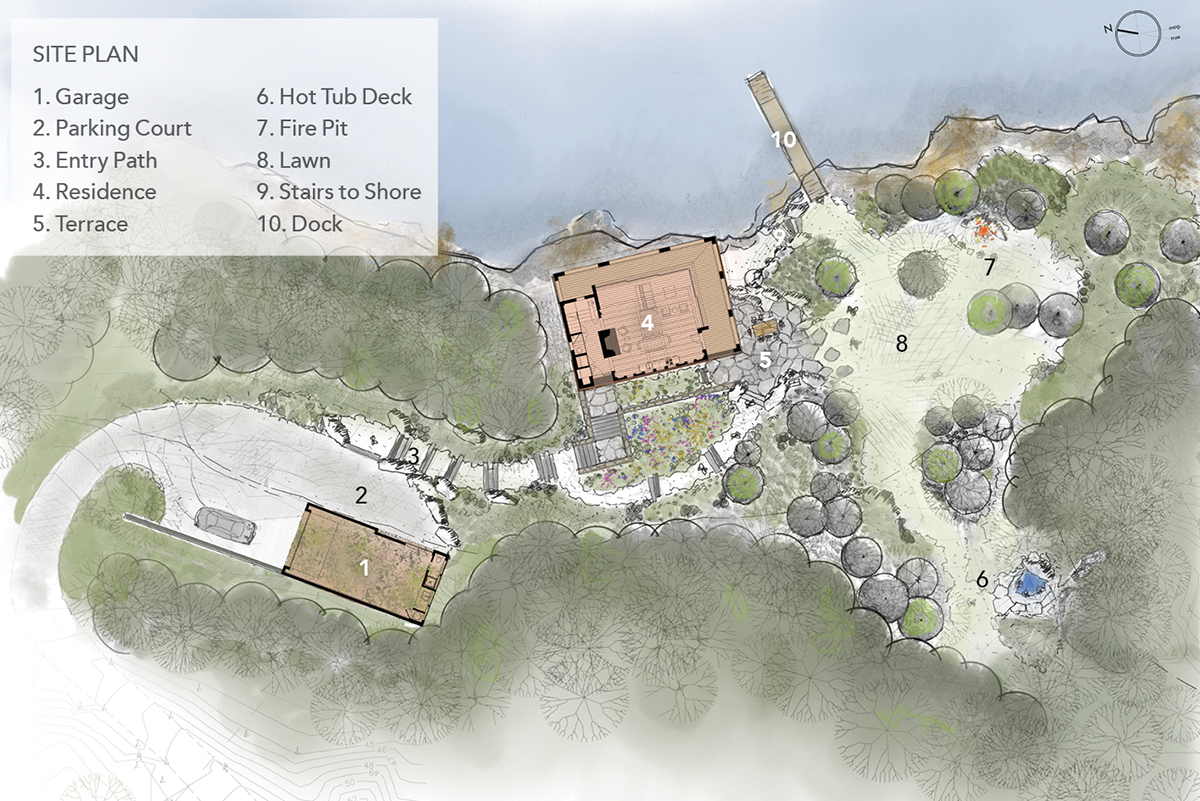

Contributing to the calm is the clients’ embargo against any parking close to the house. Visitors and owners arrive high on the wooded site and work their way down on foot to the seaside along landscaped paths. Those paths morph into stone terraces for al fresco dining and forest bathing, with bay views never out of sight.

“Previously, the driveway came all the way down with a little turnaround by the stone,” says Corey. “The construction crew had to work their way back out.” At the top of the site, a green-roofed garage/workshop building clad in Shou Sugi Ban hides offending vehicles and other undesirable intrusions.

Old Yacht Club

East Blue Hill, Maine

Architect: Matt Elliott, AIA, principal in charge; Corey Papadopoli, project architect; Buzzy Cyr, Maggie Kirsch, Elise Schellhase, project team, Elliott Architects, Blue Hill, Maine

Builder: Hewes & Company, Blue Hill, Maine

Landscape Architect: Todd Richardson, Richardson & Associates, Saco, Maine; Atlantic Landscape Construction, Ellsworth, Maine

Lighting Design: Peter Knuppel, Peter Knuppel Lighting Design, Sullivan, Maine

Project Size: 2,064 square feet

Site Size: 4.3 acres

Construction Cost: Withheld

Photography: Trent Bell Photography (new construction); Ken Woisard (existing photos)

Key Products

Cabinetry: Vipp (kitchen); custom, designed by Elliott Architects and built by Hewes & Co.

Cabinetry Hardware: Blum

Cladding: Easter white cedar shingles, existing stone veneer (repointed and rebuilt as required); Shou Sugi Ban cypress (garage)

Cooktop: Pitt

Countertops: Absolute black granite (bar); Caesarstone (primary bath); teak by Bath in Wood of Maine (forest bath)

Dishwasher: Fisher & Paykel (kitchen); Asko (pantry)

Door Hardware: Tecnoline; Ashley Norton

Engineered Lumber: Weyerhaeuser

Entry Doors: Upstate Door (front door); Marvin (kitchen entry door); Schuco lift slide doors

Faucets: Vipp (kitchen); Grohe (bar); Brizo (powder; primary; ocean bath); Kohler (forest bath)

Flooring: Roasted birch wood by AE Sampson; Cle wall tile (primary bath); Landmark Ceramics (bath floors)

Garage Doors: PDQ Door Company

Insulation: Corbond (house roofs); Roxul (walls); ZIP System sheathing

Lighting Control: Lutron

Other Exterior: Boral soffits and exterior trim (house)

Paints/Stains: Cabot; Benjamin Moore; Farrow & Ball

Refrigerator/Freezer: Sub-Zero (under stair); Summit (pantry)

Roofing: Copper standing seam (house); EPDM with green roof (garage)

Toilets: Duravit

Underlayment/Sheathing/Weatherization: AdvanTech; Grace Ultra Underlayment

Washer/Dryer: Electrolux

Water Filtration: Grohe

Windows: Marvin (house and garage); Schuco (dormer glazing)

Window Wall Systems: Schuco lift-slide doors