Creative Collaborations | Risa Boyer Architecture, Portland, Oregon

The projects of Risa Boyer Architecture are distinct in their siting, massing, design, and materiality, but they share a similar scale—one that is approachable and unassuming. Not surprisingly, firm founder and principal architect Risa Boyer Leritz, AIA, was drawn to the design profession after attending an exhibition of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian houses at the Marin County Civic Center, also designed by Wright, in California. “I was around 10 or 12 at the time, but something about the scale of those little residential units attracted me,” Risa recalls.

Growing up with an artistic family in the Napa Valley, surrounded by wood-clad, post-and-beam houses, now generally described as Midcentury Modern, Risa naturally formed a design aesthetic at a young age. “My parents were very supportive of everything I did,” she says, “and when I had started to show an interest in architecture, my mom leaned into it, probably to steer me toward a career.”

Her mother’s instincts paid off. After Risa earned her Bachelor of Architecture degree from the California College of Arts and Crafts (now the California College of the Arts), she would go on to build an award-winning design firm in Portland, Oregon, focused on modern and sustainable residential architecture and interior design. Along the way, she found inspiration and purpose from other architects and grew—and befriended—a sizable base of clients and collaborators.

Learning From Leaders

During her last year of college, Risa began working at Tanner Leddy Maytum Stacy Architects (now Leddy Maytum Stacy Architects), in San Francisco; she joined the staff after graduation. Although Risa appreciated the firm’s design process and office culture during her tenure, the influence of founding principals William “Bill” Leddy, FAIA, and the late Marsha Maytum didn’t truly hit her until she saw the business and life partners again years later at a conference. “Bill and Marsha really influenced how I run my firm today,” Risa says.

While Risa had worked more directly with Bill while at the firm, Marsha was the one who had left a lasting impression. Risa admired her vibrancy, leadership, and strength in the then male-dominated office and profession. “She carried herself well in that environment,” Risa recalls. “She was strong and kind. Her design sense stood out to me, and she was a pioneer in sustainable building.”

What also struck Risa was Marsha’s deftness at advancing her career and her firm while raising her then-young children, who would often visit the office. After leaving LMSA in 2000 and working at several smaller firms in Los Angeles, Risa started RBA in 2006. “I wanted to have kids, be able to spend time with them, and have an architecture career,” she said. The prevailing office culture and long working hours at a conventional firm, she believed, would not be conducive to her goals.

Two years later, after making inroads in Los Angeles, Risa and her husband decided to uproot everything and move to Portland, where they could grow their family nearby other relatives. It was, of course, the height of the Great Recession.

Although she could sustain her business on a few outstanding projects in California, Risa knew she had to establish her practice locally. A self-proclaimed introvert, she pushed herself to network and made several contacts through a group of mom-owned businesses. Slowly, but surely, her then two-person firm “inched our way out of the recession,” she says.

Thriving in Work

Today, RBA comprises four designers, all of whom happen to be women. “We have a nice atmosphere in the office,” Risa says. As offices began to reopen when the COVID-19 pandemic waned, “everybody wanted to come into the office right away,” she continues. “We all wanted to be together and collaborate in person.”

Half of RBA’s clients come from referrals and the other half through its website, social media, and publications. “The theme that connects them all is that they’re good people who want to work with us in a collaborative way,” Risa says. “What I love about residential architecture is that [our relationship with clients] grows with the project. We’re working with them for a couple years on such an intimate thing as the place they’re going to reside. You learn so much about them through the process that informs the architecture.”

The majority of RBA’s projects are in Oregon, but the firm has also developed a pocket of clientele in Bellingham, Washington, where Risa has found a trusted builder and friend in Jerry Richmond, owner and founder of Indigo Enterprises Northwest.

RBA’s project load is divided about equally between new construction and remodels. For the former, RBA begins the design process by studying the site, potential limitations such as wetland areas or high bedrock, and how a house can leverage the best views. Risa says many clients who are drawn to RBA are creatives themselves and come bearing a list of needs and even sketches. Still, her team relies on open dialogue and conversation to understand their clients and their vision. “Their list tells you one thing,” Risa says, “but talking to them really tells you a lot more.”

As the firm begins to develop the design with their client, it also stays mindful of the project budget. “Budget is something that we take seriously,” Risa says. “We educate our clients early on about what is a realistic budget” for their project goals. And price does not necessarily correlate with quality, she notes. “You can have the highest cost of construction and end up with a terribly built building. They’re not one and the same.”

Following in the design principles and values of LMSA, RBA prioritizes energy performance and sustainability. The firm is a big proponent of specifying tight building envelopes, high insulation values, and heat- and energy-recovery ventilators to cycle in fresh air while minimizing energy loss.

Its commitment to designing high-performance projects is bolstered by the Washington State Building Code, the latest version of which requires most residential projects to meet the 2021 International Energy Conservation Code. The mandates have helped save energy-related features—such as continuous exterior insulation—from being value engineered out. For her part, Risa believes these features offer good value for a relatively modest expense. Several contractors for RBA’s Portland-based projects have also warmed to the idea of including more high-performance features, such as those listed in the Passive House building standards.

Risa aspires to design a certified Passive House in the future, and RBA architect Valerie “Val” Reynolds is already a Phius Certified Builder. For now, the firm is content with integrating sustainable principles with design in a manner that clients can choose to notice—or not. Although clients might initially worry that sustainability relegates them to solid walls and boxy volumes, Risa says that’s not the case at all. “We like big windows on our projects too,” she notes, adding that RSA projects typically feature expansive windows of double- or triple-pane glazing—taking in panoramas of Puget Sound and other uplifting sights.

Materially Speaking

In addition to Frank Lloyd Wright, Risa points to the handcrafted quality, texture, and forms of Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer and Wright apprentice and renowned architect John Lautner as influential to her design aesthetic. Favorite materials include Cor-Ten steel for exteriors; black powder-coated steel for interiors; and concrete and smooth-troweled plaster for their minimalist look and malleability. Given their location in the Pacific Northwest, RSA projects often integrate wood structural elements, millwork, and finishes. Rough-hewn cedar siding and rift-sawn walnut and white oak, in particular, “lend themselves well to Midcentury design,” Risa says.

At the Nathan residence, a remodel that was Risa’s first client work in Portland, the prevalence of wood complements the owners’ collection of American Midcentury furniture. A custom, handcrafted walnut screen separates the entrance from the dining room while offering a contrast to the vertical grain fir of kitchen cabinets and a vintage wood dining table by Van Keppel and Green for Brown Saltman. RSA replaced the existing dark wood floor with light-colored terrazzo to brighten the interior. Portland Monthly published the project, giving Risa’s nascent firm a boost in her new home state.

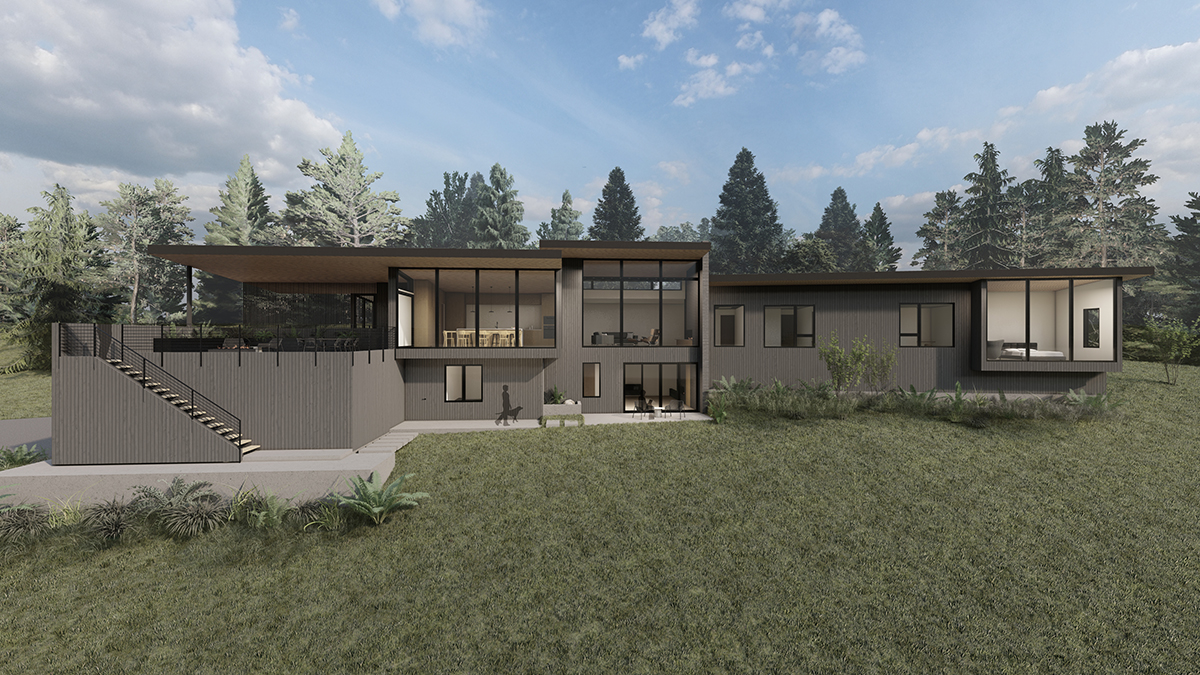

Riverwood, Risa’s first new construction project in Portland, is a 6,242-square-foot residence that hosts multiple family generations. The design’s strategic massing and setbacks enable views to the Willamette River from nearly every room. “The clients were fantastic and creative people who wanted a minimalist box,” Risa says. At night, the house’s black-painted exterior disappears into the darkness and shadows of the surrounding trees.

RBA used concrete to create a feature element in Academy Highlands, the firm’s first project in Bellingham. A minimalist, cast-in-place concrete fireplace anchors an open living space that offers panoramic views of Whatcom Lake. Moreover, “everybody enjoyed working together,” notes Risa, who had recently returned from a Bellingham trip where she visited former clients and her builder Jerry Richmond.

Going Commercial

For the time being, much of RBA’s portfolio is residential, but the firm also takes a few commercial projects. One example is the mixed-use infill project her office currently occupies. The project replaced a rundown house on an awkward lot, Risa says. “Nobody wanted it. It was a strange, L-shaped property with a courtyard in the center on a commercial street that didn’t have much new development happening on it yet.”

The opportunity was too good to pass up for Risa and her husband, who had always talked about developing a property together. After purchasing the property in 2014, they opened Makers Row in 2017. The energy-efficient, mixed-use project comprises 19 apartments and two commercial spaces across two perpendicular volumes, allowing natural light to reach all units and building elevations. Its tight building envelope and use of highly insulated window units from Canada helped earn the project recognition from the nonprofit organization Energy Trust of Oregon.

More to Come

Nearly 20 years into her own practice, Risa tries to impart lessons from her own experience to her team. She can still remember days ruined by the everyday setbacks that architects encounter, particularly early in their career—a delayed building permit or a mistake in the field. “I would think, ‘This is the end of this project,’ or ‘I should have known about that,’” she recounts. “Now, I know it’s going to be OK. It might not be as perfect as everybody thought, but it always works out.”

Risa also hopes to grow her full-service architecture firm in new directions. She has added furnishings to its capabilities, which already included finishes, lighting, and cabinetry design as part of its standard scope. By collaborating with her clients on furniture selection, she believes they will enjoy the benefit and the “fun of having a cohesive space in the end.”

She also plans to continue implementing more Passive House design strategies into the firm’s projects to show how naturally sustainable design principles suit good architecture. Her ability to drive her clients and the building industry toward an increasingly higher level of energy performance is one reason she continues to enjoy architecture. “Architects have a huge impact on the environment,” Risa says. “We can turn that into having a positive impact on the environment. That’s exciting to me—that we can have that much influence on it.”

Residential Design has previously published two case studies by Risa Boyer Architecture:

- Academy Highlands in Bellingham, Washington

- Glen Road in Lake Oswego, Oregon